Research study from the 1980s.

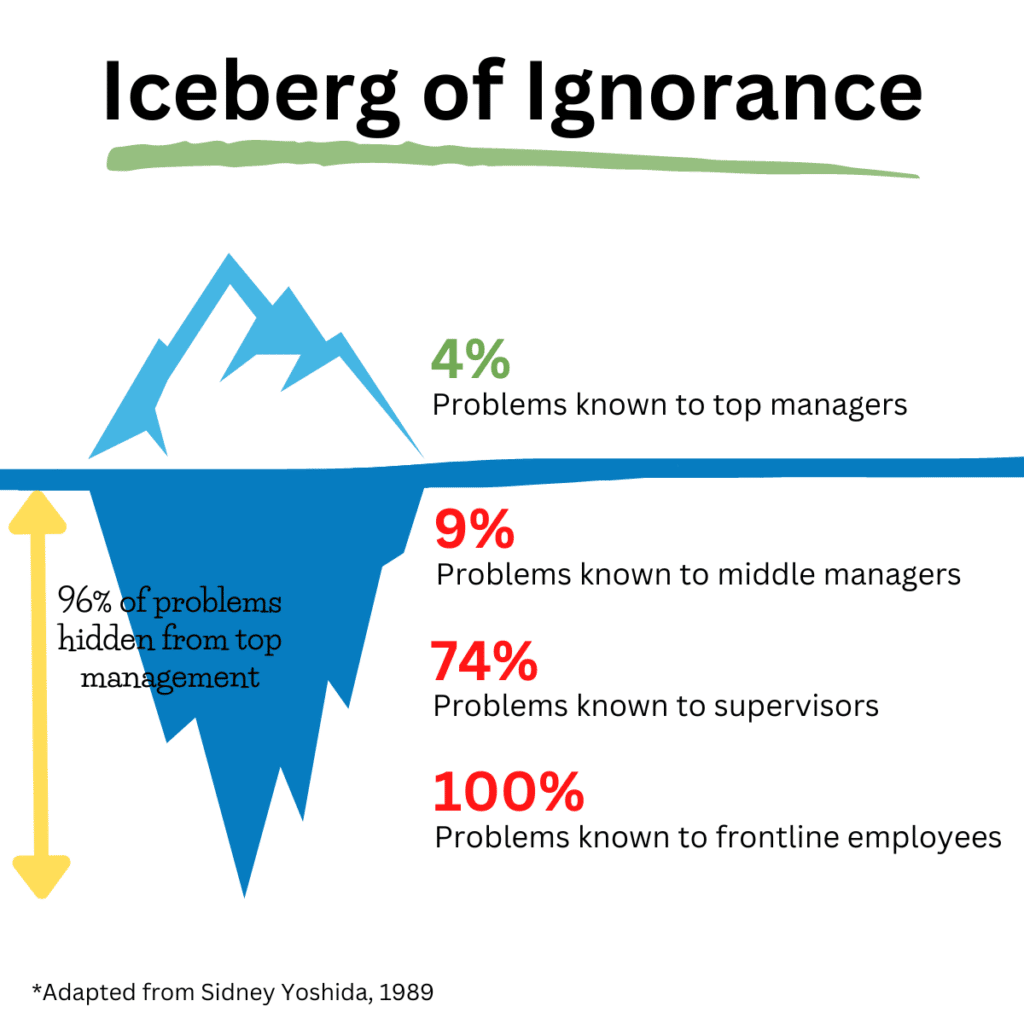

You’re no doubt familiar with pictures and sketches of the so-called ‘Iceberg of Ignorance’ that continue to captivate on social media. It seems it has become a popular leadership legend from the 1980s management research literature.

The Iceberg of Ignorance originates from a large 1989 research study by the Japanese consultant Sidney Yoshida. The iceberg represents Sidney Yoshida’s key findings after having researched the work and leadership habits and culture of a Japanese car manufacturer, Calsonic.

Allegedly, he found that only 9% of frontline problems were known to middle managers and as little as 4% were known to the executive top management[1].

That means that 96% of the frontline problems known to the frontline employees were unknown or hidden from the executive top management. Or simply put, the top managers were only aware of the tip of the iceberg.

The reason for that was issues with the hierarchical power structures and distribution of information cross-organizationally. It meant that as Sidney Yoshida went further up the organization, frontline problems became less known to management.

Now, the question is whether this old data is still relevant and would show the same in today’s modern leadership contexts?

I think it depends on the organization and culture.

Let me in the next section talk about some useful strategies you as a manager can use to communicate better with your frontline employees and listen to their problems and experiences.

4 key strategies for leaders to avoid steering their ship into the Iceberg of Ignorance.

Luckily, there are different approaches managers on all levels can take to cultivate a culture of listening, communication, and feedback about problems, issues and solutions to become more aware of the metaphorical territory rather than the map.

Below, I will run you through four different strategies you as a manager can use to understand your people and the real work better and make it real:

1. Frequently engage with frontline employees:

Firstly, it is about role modelling what I call ‘Present Leadership’ as a manager. It means that you develop a leadership presence where you quiet your mind and remains open and authentic to other people. That entails to be fully present in the moment when interacting with peers and employees, e.g. listening with an open mind.

To better understand frontline problems it is also key to engage with your frontline employees. So, managers have to build stable relationships with their frontline employees by being genuinely interested in them as people, in their work, effort and impact. You can make that real by establishing frequent informal meet-ups and feedback loops and however banal it may sound by showing up where your frontline employees do the work and talk to them. It also works in a hybrid work context.

2. Practicing go to Gemba:

The term Gemba stems from Japanese and means “the real place”[2]. In lean management going to Gemba or the Gemba walk was developed by Taiichi Ohno who is considered the founder of Toyota’s lean manufacturing[2]. Gemba is the most important place to be because it is where the value-stream is. A Gemba walk therefore offers managers on all levels to see where the real work happens and build trusting relationships with their frontline employees, which is crucial to understand the frontline issues and problems[2].

The main important parts of a Gemba walk are[2]:

- Go and see. Managers on all levels should take regular walks around the shop floor where the frontline employees work. Managers are involved in the collaboration to find wasteful activities to continuously improve.

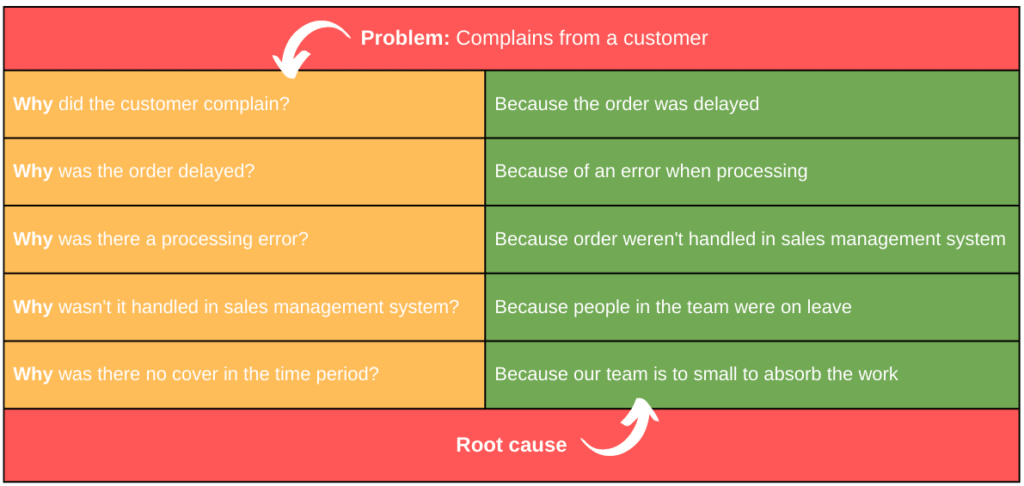

- Ask why (the 5 whys). The main point of a Gemba walk is to explore the value stream in detail and locate the problematic parts through active listening and communication. As a manager, it is very easy to become solutions-oriented and wanting to fix things right away, but instead try to be curious and eager to listen to understand.

Using the 5 whys, can help you better understand a situation or problem and find the root cause to them. Below you find an example on how to apply the 5 whys as a manager.

In my experience from coaching the use of the word “Why” sometimes can come across as accusing or it can be perceived like that. To avoid that, because we want a non-judging atmosphere, it can be interchanged with “What”, e.g. What made the customer complain?

- Respect people. In a Gemba walk remember to keep an open mind, so it is not about blaming, pointing fingers or judging your frontline employees but a collaboration to find the weak spots and root causes of problems and processes together.

3. Leading with humility:

A great approach managers can integrate with Gemba walks, is to adopt a humble mindset of a servant leader, who focuses on helping their employees feel purposeful, motivated and energized[3].

Servant leaders lead with humility by serving employees as they explore and grow by creating a culture of learning by actively seeking ideas and unique contributions from the employees[3].

In his great Harvard Business Review article, Dan Cable articulates servant leadership brilliantly[3]:

“servant leaders have the humility, courage, and insight to admit that they can benefit from the expertise of others who have less power than them.”

So, if we connect that leading with humility to the Iceberg of Ignorance, it is clear that managers on all levels need to acknowledge that they can learn so much from the expertise of their frontline employees.

And they need to be humble, genuinely present and they have to prioritize time with frontline employees to really understand all of the frontline problems. That is how managers can gain insights about how they can best support their frontline employees do their jobs even better[3].

“Servant leaders have the humility, courage, and insight to admit that they can benefit from the expertise of others who have less power than them.”

Dan Cable

4. Creating psychological safety:

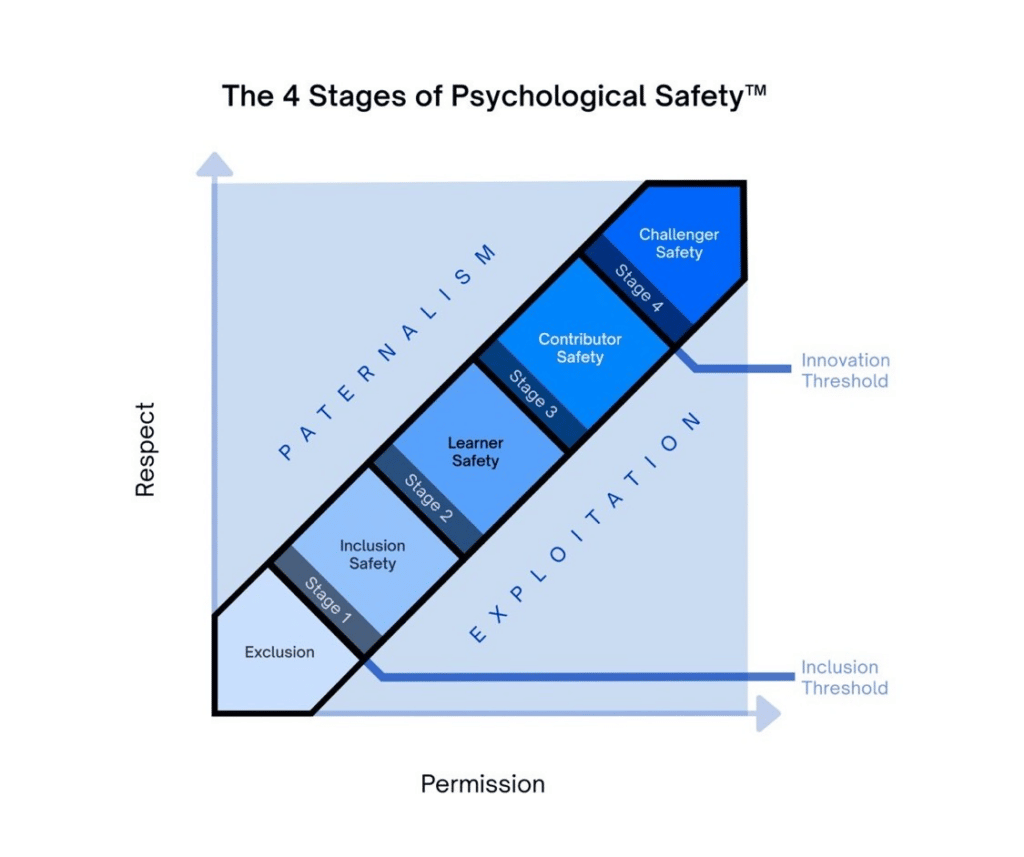

Creating high-trust environments where employees feel psychologically safe is the foundation to having better feedback loops, openness about problems and understanding of what is really happening.

Psychological safety is a space where you can openly speak up and be vulnerable without the risk of punishment, retribution or humiliation[4].

Building on the previously described servant leadership, some of the best ways to serve employees overall, and in this case specifically frontline employees, is to create low-risk spaces to experiment[3]. Spaces where employees can experiment with their ideas, make mistakes and feel comfortable sharing them and be vulnerable without retribution.

Timothy R. Clark outlines how psychological safety can be fostered in 4 stages as shown below[5]:

- Inclusion Safety: Can I be my authentic self?

- Learner Safety: Can I grow?

- Contributor Safety: Can I create value?

- Challenger Safety: Can I be candid about change?

If we zoom in on Learner Safety, having low-risk environments where employees feel safe to fail and experiment are important to learn and grow. Interestingly enough, a 2019 research study at the University of Arizona shows that the optimal sweet spot for creating motivation and learning is 85% success and 15% failure rate[6,7].

So, if you never fail, you will not be challenged enough to continue, while if you fail too frequently, you become demotivated[6]. Now that means, if you fail 15% of the time, you will continue to come back for more[6].

This approach is called the ‘85% rule’ and to make it real, it is useful to have different approaches to goal-setting.

All of that relates to the importance of humble servant leadership to create low-risk environments of psychological safety where people can have that success-failure ratio right and are motivated because they can fail and want to share their mistakes without punishment.

Therefore, a genuine interest in your frontline employees and frontline problems from all leadership levels is key.

Read more here about psychological safety in the context of Quiet Quitting.

Now let me hear your reflections:

- What do you think the Iceberg of Ignorance data would show today?

- What’s your best strategies you want to add to melt the ice?

I have now shared 4 strategies that you as a manager can use to enhance communication with your valuable frontline employees. If you need help as a manager to think about ways you can integrate that in your organization, then I am here to partner with you as your Coach.

Here you can learn more about our Leadership Coaching and Team Coaching.

Please feel free to contact me if you want to learn more about Coaching.

References.

[1]Yoshida, S. (1989) Quality improvement and TQC management at Calsonic in Japan and overseas. Second International Quality Symposium, Mexico.

[2]Kanbanize (2023) Gemba Walk: Where the Real Work Happens. Available at: Gemba Walk: Where the Real Work Happens (kanbanize.com). (Accessed 15 January 2023).

[3]Cable, D. (2018) How Humble Leadership Really Works, Harvard Business Review. Available at: How Humble Leadership Really Works (hbr.org). (Accessed 15 January 2023).

[4]Edmondson, A. C. and Mortensen, M. (2019) What Psychological Safety Looks Like in a Hybrid Workplace, Havard Business Review. Available at: What Psychological Safety Looks Like in a Hybrid Workplace (hbr.org). (Accessed 25 September 2022).

[5]LeaderFactor (2023) What is Psychological Safety? Available at: https://www.leaderfactor.com/psychological-safety (leaderfactor.com). (Accessed 10 January 2023).

[6]Brower, T. (2021) Learning Is A Sure Path To Happiness: Science Proves It. Available at: Learning Is A Sure Path To Happiness: Science Proves It (forbes.com). (Accessed 25 January 2023).

[7]Wilson, R. C., Shenhav, A., Straccia, M. and Cohen J. D. (2019) The Eighty Five Percent Rule for optimal learning, Nature Communications 10, 4646. Available at: The Eighty Five Percent Rule for optimal learning (nature.com). (Accessed 25 January 2023).