Entering the new year 2024, organizations continue to have a strategic focus on bringing in the best talent.

Simply because better talents are up to eight times more productive than average employees at very high complexity work[1]. That means that the quality of talents directly impact the organizational performance[1].

Therefore, it is critical for organizations anno 2024 to be able to identify, attract, develop and retain high-performing talents as a means of achieving their organizational and strategic targets.

You can even argue that instilling a shared organization talent mindset — a shared belief that diverse, better talent elevates organizational performance and is a great source of competitive advantage[2] — has become even more crucial in times of change, uncertainty and ambiguity for leaders in all leadership roles.

Talent is all leaders’ responsibility.

So, it’s key for all leaders in organizations to become passionate about and accountable for strengthening their own and peers’ talent pools. If you are a leader it is critical for long-term organizational success to be able to spot (and have engaged development conversations to understand) where each human being can bring the most value to the organization while having meaningful and fulfilling careers.

Too often, the silo-thinking mentality occurs, not out of bad intentions, but because you as a leader want to do well.

You want to excel in your role and deliver great results together with your team as an effective leader.

Hence, you may become reluctant to let your high-performing talents go, so you are able to continue delivering great results.

Even if your talented employees might bring more value to the organization in another role and contribution.

They may even have passions, talents and potential that are better realized elsewhere. Maybe even outside your organization.

In this blog article, I will discuss talent and potential and how leaders and organizations can consider it.

Over the holiday season, I had the pleasure of finishing Adam Grant’s brand new book “Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things”.

Adam Grant is a well-known organizational psychologists at The Wharton School and a best-selling author. I also recommend his other books “Give and Take” and “Originals”.

I enjoyed reading his new book about hidden potential because it rethinks ways to elevate ourselves as well as others. Adam Grant tells inspiring stories about discovering and nurturing potential in amazing chess teams, mountaineering, school systems to astronauts.

In the book Adam Grant provides insights into how to build the character skills and motivational structures needed to realize your own hidden potential. Furthermore, how to design foundational systems that create opportunities for people who have been underrated and overlooked.

In my opinion, the book offers a fresh perspective on potential and talent that can inspire organizations and yourself. Let’s dive more in!

Human Talent and Potential.

Most organizations have an annual process for reviewing, challenging and future-proofing their needed capabilities (supply and quality of talent; often focused at leadership talent) long-term to achieve the strategy.

Often, it is referred to as an Organizational Review, Talent Review or People Review.

It is a subjective evaluation by every leader of their team’s capabilities as well as succession. It is then often calibrated and challenged between members of the management team.

Potential and Performance are typically reviewed using the so-called 9-box grid. The grid scales from low-high performance and low-high potential to advance as shown below in figure 1.

In an organizational context, in essence, Talent is characterized as the intersection between Performance and Potential, meaning high performance over time and high potential to advance in the organization.

When organizations establish their standard for talent and potential, it’s ideal to consider:

- What does great talent and potential look like?

- What is talent and potential for leaders?

- What is talent and potential for specialists?

- Potential for what? (meaning in what context, e.g. to advance organizationally as a leader etc.)

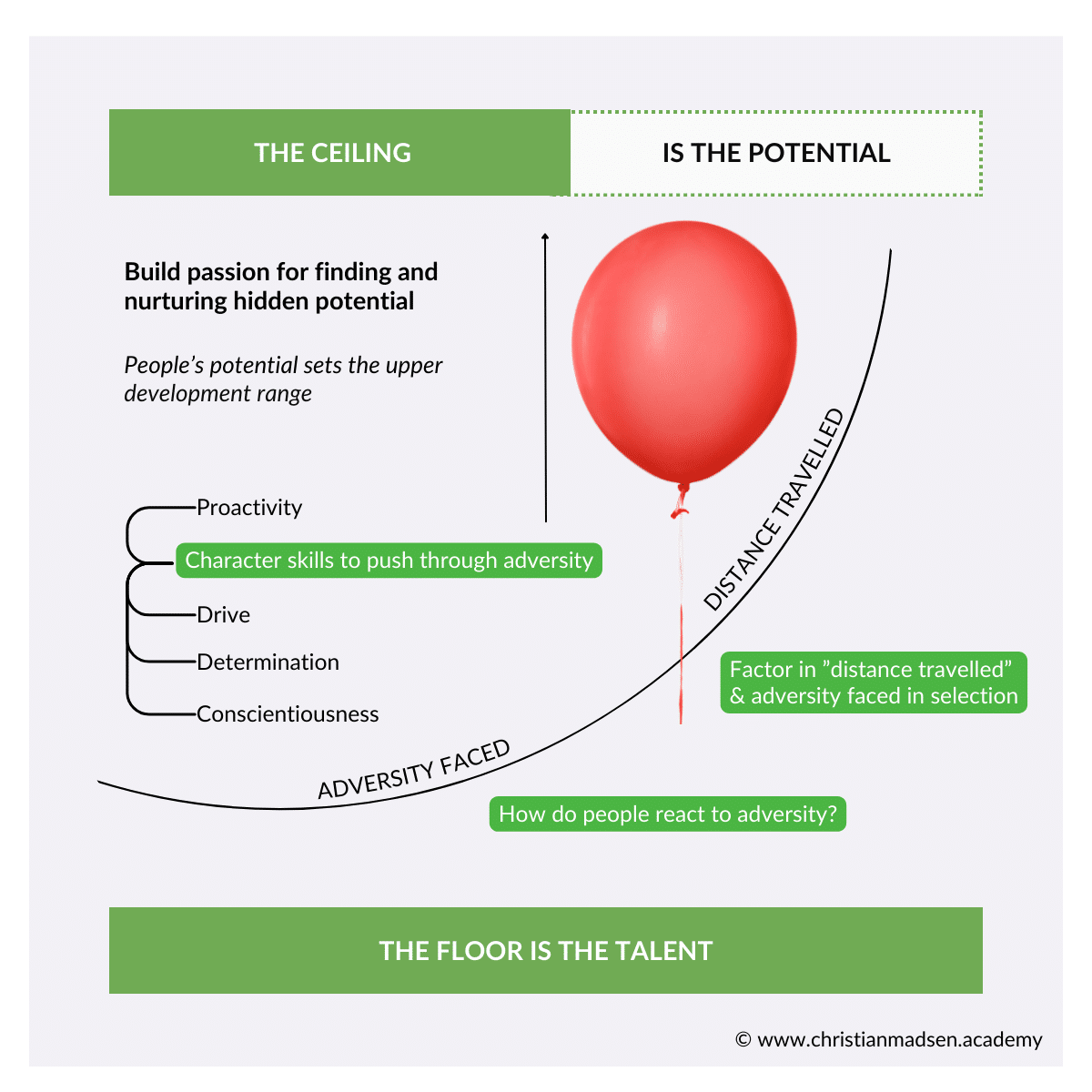

In his book “Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things”, Adam Grant uses a great metaphor to destinguish Talent and Potential.

Talent is the “floor”, the starting point, whereas Potential is the “ceiling”, people’s upper development range as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

I like this metaphor for three reasons (see Figure 2):

- It highlights the importance of considering the “distance travelled”, i.e. performance over time and adversity faced

- Character skills are key: Proactivity, drive, determination, conscientiousness help push through adversity

- The “ceiling” captures context well (what is the potential to advance in the role, the organization etc.?)

It is great to see how Adam Grant highlights adversity as an element to consider when it comes to potential[3]. He writes that people also need structures, so-called temporary support structures (termed scaffolding) to sustain motivation and resistance amid struggles and challenges to overcome obstacles that threaten to overwhelm us and limit our growth[3].

Noun: Adversity

The Oxford English Dictionary

a difficult or unpleasant situation.

Ex. “Resilience in the face of adversity”.

These “scaffolding” mechanisms can help in productively overcoming adversity faced but the mechanisms put in place by individual employees for themselves also tells a lot about their character and potential[3].

Adam Grant suggests using deliberate play (making practice more fun, varied and playful) as one scaffolding option to sustain motivation (temporary support)[3]. Another kind of scaffolding is teaching others in a subject matter to thereby increase own learning[3].

Organizations can focus on the same points.

What temporary support interventions can we offer to employees to help them build the resistance needed to overcome adversity.

Consider how people react to adversity; Do they give up? Do they change direction? Or do they push through it, learn from it and improve their performance over time (distance travelled)?

It is refreshing to see that focusing on strenghts and people that are already performing at a high level can cloud our vision, so we overlook the great potential of the people that are facing challenges, are struggling, overcoming and pushing through adversity over time.

However, how people react when facing adversity can be difficult to measure.

So, looking into people’s journey of overcoming difficult challenges, handling discomfort and learning is definitely worthwhile when we talk about potential.

In the next part, I’ll connect it with some data-driven measures as inspiration.

Data-driven identification of Talent.

In their excellent Harvard Business Review article called What Science Says About Identifying High-Potential Employees, the authors argue that scientific studies have for long suggested that investing in the right people will maximize organization’s returns[4].

Therefore, it’s key to be able to identify high potentials and talents well to be able to predict who is likely to become the key drivers of organizational performance[4].

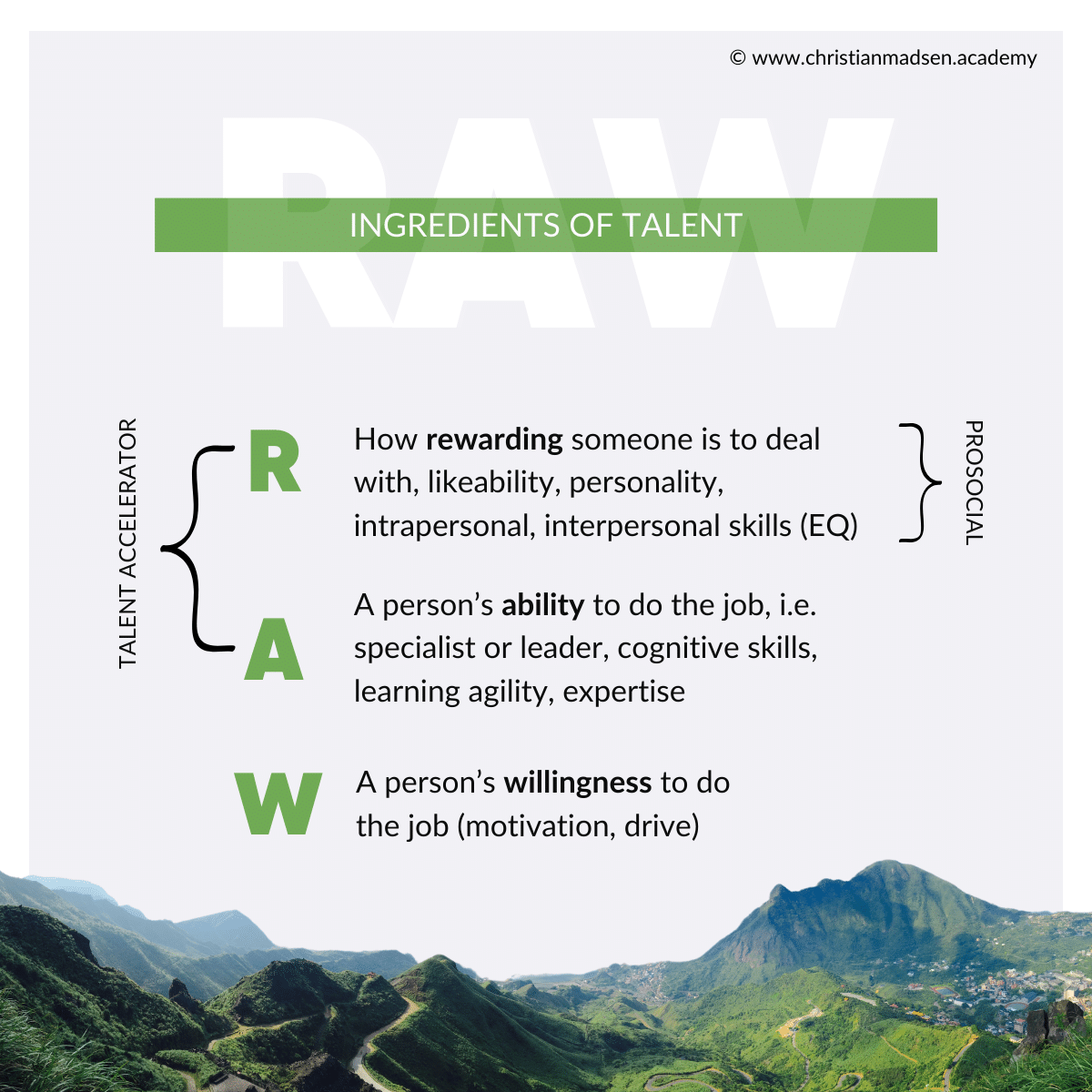

In his great book “The Talent Delusion: Why Data, Not Intuition, Is the Key to Unlocking Human Potential”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic offers an excellent simplified and science-based model to identifying Talent and Potential, rightly called the RAW Ingredients of Talent outlined in Figure 3 below.

It’s a valuable model, so let me break it down for you.

The RAW model focuses on what you can measure and it consists of the following parts (Figure 3):

Rewarding — a person’s likeability and how rewarding someone is to deal with. It’s a function of personality and concerns intrapersonal skills (managing yourself) and interpersonal skills, the ability to manage others (relationships), which are both the core elements of emotional intelligence (EQ)[4,5].

This can be captured as social skills or prosocial skills as Adam Grant terms it in his book Hidden Potential[3]. So, emotional intelligence can be seen as an early indicator of potential, which can be assessed in psychometric tests[4].

Able — A person’s ability to do the job[5]. It’s about demonstrating the knowledge and skills required to perform the key tasks of a job[4]. The sub-components of ability are expertise; domain or job-related knowledge, experience and skills and intelligence, which includes learning ability and reasoning potential[5].

The leading predictor of job performance is a job sample test and the best predictor of the ability to learn and master the skills is IQ or cognitive ability[4]. Here, it is worthwhile to consider how people’s performance has developed over time across several challenging scenarios or roles (distance travelled as Adam Grant describes it in his book Hidden Potential). It is also key to consider specialist transition and leadership transition frameworks to clearly point out the performance standards of each role.

Willing — A person’s willingness and motivation to work hard to do the job[4,5]. It relates to someone’s ambition, drive or conscientiousness and a person’s work ethics[5]. It’s about having the willingness to push through some discomfort to build the skills or experience needed to do a job[4].

If you are both rewarding to deal with and able, these two factors are a talent accelerator[5]. The more you have of it, the more your talent will grow[5]. A great way to measure willingness or drive is using standardized tests measuring conscientiousness, ambition and achievement motivation[4].

In this connection Talent can be perceived as being able and rewarding to deal with (prosocial skills)[4]. It can also be characterized as effortless performance[5], while Potential can be perceived as talent plus effort or talent multiplied by will and drive as it determines how much your ability and prosocial skills get put to use[4].

If we relate that to Adam Grant’s points in his book Hidden Potential, the determination, proactivity and character skills needed to push through, respond productively and overcome adversity[3] fit well with willingness from the RAW model.

Drive can also be related to the drive for learning, so being hungry for learning something, making mistakes and improving. Adam Grant uses a great metaphor in his book of being like a human “sponge”, which is relevant to consider.

Try using these components and look at what adversity people have faced and how they’ve handled it as well as their performance over time (distance travelled).

So, how do you as a leader encourage your team to discover their true potential?

One place to start is to get to know your team members really well and uncover their interests, where they struggle and their passions.

In my experience these conversations can become a bit superficial, so try to dig deeper. Discover and explore together.

Consider using these 5 guiding questions as a starting point:

- What excites you most at work?

- What do you really want to learn?

- Which tasks have been challenging for you previously and now?

- What superpowers have you noticed about yourself?

- What do you truly enjoy doing outside work?

Remember.

Strengths are one thing → Try to explore what is challenging.

Your potentials may be elsewhere than where you are highly skilled right now.

Potentials may lie in how and where you face and overcome adversity.

P.S. What is talent and potential for you? Share your thoughts in the comments.

References.

[1]Keller, S. (2017) Attracting and retaining the right talent. Available at McKinsey (mckinsey.com). (Accessed 14 December 2023).

[2]Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H. and Axelrod, B. (2001) War for Talent. Available at: Harvard Business School (hbswk.hbs.edu). (Accessed 14 December 2023).

[3]Grant, A. (2023) Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things, WH Allen, London: pp. 1-246.

[4]Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Adler, S. and Kaiser, R. B. (2017) What Science Says About Identifying High-Potential Employees. Available at: Harvard Business Review (hbr.org). (Accessed 14 December 2023).

[5]Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2017) The Talent Delusion: Why Data, Not Intuition, Is the Key to Unlocking Human Potential, Piatkus, London: pp. 1-233.